All but the most myopic of comic fans can see that the writing is on the wall for comic shops.

Amazon and online book retail, the graphic novel or trade paperback finding shelf-space in high-street bookshops (like Waterstones and Barnes & Noble), the proliferation of free comics online (legal and not so legal), the move away from print and the development of web-native formats are besieging these grubby palaces of pre-pubescent fantasy.

But should we mourn the passing of comics shops or speed it up?

Many years ago I worked in a shop called Comics Showcase, on Neal Street, in London. This was a geek’s paradise, with walls covered in stupid toys and Golden Age and Silver Age comics in plastic cases, presided over by a cast of grotesques. I loved comics madly, but even I could see that comprehensive knowledge of the history of X-Force and WildCats was useless in any environment other than the comic shop.

When I say that stereotypes are stereotypes because they are largely true, I mean that they accurately mirror a cultural view of their subjects, with all the prejudices and biases entailed. There is a reason why the stereotypes of comics fanboys and comics shops are so fitting. What disturbs me is that comics readers and especially owners of comics shops are so comfortable with this stereotype, that they do nothing to challenge it.

Despite the fact that comics have changed hugely over the past twenty years, to comprise a much larger and more diverse readership, the most insular, immature and vocal constituency of comics culture continues to determine the way comics are perceived on a wider cultural level.

I was shocked to hear on a recent Comic Cast podcast that Irish comics creator Bob Byrne was unable to get an Arts Council publication grant for his graphic novel, Mr. Amperduke. This, despite Byrne’s being the first Irish comics creator to gain international distribution from Diamond for his work, despite producing a graphic novel which has put Ireland on the map.

Happily Byrne has gone on to successfully self-publish the graphic novel. But it points to a serious problem about the way comics are perceived. The US leads the way in terms of accepting comics as a serious medium and there you can find not only the superhero staples, but also more literary comics and graphic novels and small-press work.

Before the 1980s you bought your comics at a newstand or supermarket. I bought my first comics in my local newsagent. In the current economic climate, comics retailers had better realise that comics are a medium, not merely a sub-culture, and cater to a wider group than it does at present.

Unless comics retailers reach out to a broader audience, I believe the market will die within the next few years. This would be catastrophic. As comics fans know comic shops are not just retail outlets, they are the coffee shops, exhibition halls and cultural centres of the medium.

Showing posts with label History. Show all posts

Showing posts with label History. Show all posts

17 February, 2009

02 February, 2009

Famous Artists Cartoon Course

"It's a bad idea to try to prevent people from knowing their own history. If you want to do anything new you must first make sure you know what people have tried before."

- Ernst Gombrich, A Little History of the World

I've posted all the available lessons from The Famous Artists Cartoon Course up on Issuu. Whether or not you are interested in learning to draw, the lessons are illustrated by such old-school heroes as Al Capp and Milton Caniff.

(via Comicrazys and Leo Brodie)

29 January, 2009

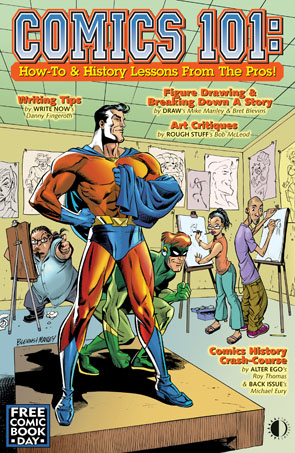

Review: Comics 101: How-To & History Lessons from the Pros!

A short primer that places cultural context at the heart of comics creation

Most manuals and ‘how-to’ books about making comics fall into three categories: the first assumes no drawing skill on the reader’s part and instructs accordingly; the second assumes some skill in drawing (and using software) and offers technical direction about combining or adding to those skills; the third, and most useful, considers comics holistically, as a cultural medium.

Most manuals and ‘how-to’ books about making comics fall into three categories: the first assumes no drawing skill on the reader’s part and instructs accordingly; the second assumes some skill in drawing (and using software) and offers technical direction about combining or adding to those skills; the third, and most useful, considers comics holistically, as a cultural medium.

Comics 101 falls into this third category. Really an extended magazine, produced by by TwoMorrows Publishing for Free Comic Book Day 2007, Comics 101... features articles by editors from several of its specialist comics-related magazines.

So firstly, there are articles on figure drawing and story layout, which cut to the point very smartly.

I also found Bob McLeod’s critique of a Fantastic Four layout fascinating and full of direct advice (‘It’s always better to design your elements using diagonals, rather than horizontals and verticals’ and ‘center the figures in the panel, then design the backgrounds around them’ and so on).

The article on writing is fairly general, but offers some good points on etiquette in dealing with publishers. But the two longest articles are potted histories of comics. The first article explains the roots of the comics medium up to the 1970s and the evolution of the super-hero genre. The second article concerns the modern era of comics, the advent of commercialisation and direct sales and the innovation of indie comics and the graphic novel.

What marks Comics 101 out as unusual is its insistence on basic skills, patient development of ideas and awareness of the historical and cultural context in which comics are created and consumed.

Of course it cannot be as in-depth as Scott McCloud's Making Comics, at just 30-odd pages, but as a freebie it is excellent value in every way.

Most manuals and ‘how-to’ books about making comics fall into three categories: the first assumes no drawing skill on the reader’s part and instructs accordingly; the second assumes some skill in drawing (and using software) and offers technical direction about combining or adding to those skills; the third, and most useful, considers comics holistically, as a cultural medium.

Most manuals and ‘how-to’ books about making comics fall into three categories: the first assumes no drawing skill on the reader’s part and instructs accordingly; the second assumes some skill in drawing (and using software) and offers technical direction about combining or adding to those skills; the third, and most useful, considers comics holistically, as a cultural medium. Comics 101 falls into this third category. Really an extended magazine, produced by by TwoMorrows Publishing for Free Comic Book Day 2007, Comics 101... features articles by editors from several of its specialist comics-related magazines.

So firstly, there are articles on figure drawing and story layout, which cut to the point very smartly.

I also found Bob McLeod’s critique of a Fantastic Four layout fascinating and full of direct advice (‘It’s always better to design your elements using diagonals, rather than horizontals and verticals’ and ‘center the figures in the panel, then design the backgrounds around them’ and so on).

The article on writing is fairly general, but offers some good points on etiquette in dealing with publishers. But the two longest articles are potted histories of comics. The first article explains the roots of the comics medium up to the 1970s and the evolution of the super-hero genre. The second article concerns the modern era of comics, the advent of commercialisation and direct sales and the innovation of indie comics and the graphic novel.

What marks Comics 101 out as unusual is its insistence on basic skills, patient development of ideas and awareness of the historical and cultural context in which comics are created and consumed.

Of course it cannot be as in-depth as Scott McCloud's Making Comics, at just 30-odd pages, but as a freebie it is excellent value in every way.

21 August, 2008

The Joker/Gwynplaine

This chap is Conrad Veidt, whose appearance as Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughed (1928) - based on the novel by Victor Hugo - served as the model for Batman's arch-enemy, The Joker.

This chap is Conrad Veidt, whose appearance as Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughed (1928) - based on the novel by Victor Hugo - served as the model for Batman's arch-enemy, The Joker.Batman first appeared in Detective Comics, in 1939, as did The Joker and Catwoman. Veidt must have made quite an impression on Kane's assistant, Bill Finger, to inspire the creation of the Joker character, a decade later.

He's creepy alright.

19 August, 2008

History of Comics/History Comics

Research never sleeps, nor do I much. I have been reading copious tracts on comics history and urban theory, with the vain hope of discovering points of correspondence. So far, not so many, but perseverence and diligence (and chastity, for some reason) are my watchwords!

Research never sleeps, nor do I much. I have been reading copious tracts on comics history and urban theory, with the vain hope of discovering points of correspondence. So far, not so many, but perseverence and diligence (and chastity, for some reason) are my watchwords! In fact there is loads of stuff about the history of comics online, but not so much about comics which take history as their subject matter. George O'Connor adapted Harmen Meyndertsz Van den Bogaert's 17th century journal as Journey Into Mohawk Country but I can't think of any others. (Suggestions please!)

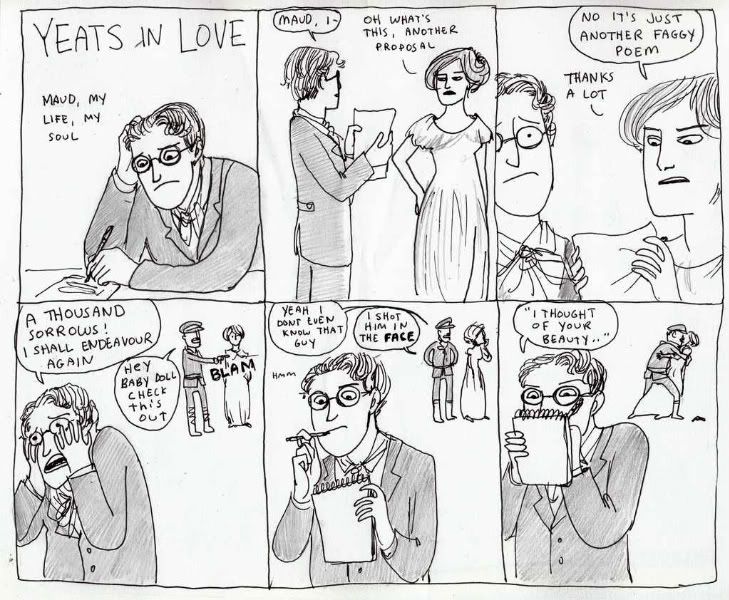

In fact there is loads of stuff about the history of comics online, but not so much about comics which take history as their subject matter. George O'Connor adapted Harmen Meyndertsz Van den Bogaert's 17th century journal as Journey Into Mohawk Country but I can't think of any others. (Suggestions please!)Three cheers then for clever Canadian, Kate Beaton, who battles low self-esteem with excellent comic strips about famous historical personages. Sure, they may not be 100 per cent historically accurate - I'm pretty sure Washington didn't exactly cross the shit out of the Delaware - but they are very funny.

15 August, 2008

Review: Mac Raboy's Flash Gordon Vol. 1

A rocket- fuelled adventure into the history of comics.

A rocket- fuelled adventure into the history of comics.Most of my reviews go well over 100 words, but I'm really going to keep to it this time. Starting now.

No wait... now.

Mac Raboy took over from his hero Alex Raymond drawing Flash Gordon for King Features Syndicate, from 1948 until his death in 1967. This volume collects Raboy's Sunday comics strips from 1948-1953.

The artwork is great on some of the strips, with great panel design and illustration. Raboy is justifiably renowned for his bold lighting effects, which give a lot of punch to the strips.

But two things particularly struck me about these Flash Gordon strips. The first was the short-form storytelling.

Although one of Flash's adventures to outlandish alien planets could be as long as a modern comic book - albeit spread out over a couple of months - these newspaper strips, with their mini-adventures and cliffhanger endings, feel like a completely different genre to modern comics.

The narrative skips a lot of action, giving the impression of fast-forwarding through the story. Lots of momentum, to be sure, but not much coherence, which must have worked just fine for weekly readers.

The second big feature was the dominance of captions and the absence of speech balloons, any emanatae or sound effects. Dialogue is in reported speech and frequently summarised in the captions.

I wonder why Raboy chose not to use speech balloons, which had been long established. From a graphical perspective it allows for nice, clean compositions, but it creates quite a static, airless effect.

Modern comics have few or short captions, direct speech between characters and lots of 'sound', which creates a lively, direct feeling to the narrative and puts the reader in the scene.

Raboy's Flash Gordon is exactly the opposite and while it is fascinating from a historical perspective, it really feels its age. This first volume, collects the earliest strips, so it might be interesting to see how the strip changed over the years.

Okay, was that one hundred words? No?

29 July, 2008

In Search of Steve Ditko

I could kick myself for missing the BBC 4 documentary, In Search of Steve Ditko, which aired last autumn.

I could kick myself for missing the BBC 4 documentary, In Search of Steve Ditko, which aired last autumn.I am currently reading a Marvel Pocket Book which collects Ditko's early Dr. Strange stories and explains how the brilliant surgeon, Steven Strange, became the even more brilliant occultist.

Dr. Strange is quite unlike any other Marvel comic. With its edgy, abstract graphics and dark themes, it's easy to see how it attracted a counter-culture following in the 1960s.

Fantagraphics recently published a critical retrospective of Ditko's work, Strange and Stranger, and there seems to be renewed interest not only in his seminal role on Spiderman and Dr. Strange, but his later (weirder) work for DC and Charlton Comics.

Apart from his great, though unusual, creative talent, the mystery about Ditko's abrupt departure from Marvel Comics and Spiderman, his reclusive character and his adherence to Ayn Rand's quasi-fascist ideology, Objectivism, all contribute to the enigma that is Steve Ditko.

There are only snippets of the BBC documentary around YouTube, so I am grateful that fellow comics enthusiast Doug Pratt has posted the full program in decent quality, in six seven-eight minute segments (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7). Thanks Doug!

BBC 4 is currently rerunning its Comics Britannia documentary series. The first program, about DC Thompson's Comics Factory - which created Beano, The Dandy, Whizzer and Chips etc - was excellent and I look forward to the next installment.

[via Paul]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)